The following is a colorful description of Moran founder Michael Moran and the chaotic tugboat industry in New York Harbor in the late 1800s. While times have thankfully changed in the marine transportation industry, we at Moran today still respect and emulate the entrepreneurial spirit of our founder and the focus on safety he embraced.

All content comes from “Tug O’ the Heart” by Marian Betancourt in the February-March 2003 edition of Irish America except where otherwise noted.

Michael Moran Comes to America

To say the Irish had a lot to do with making New York a great maritime port is no blarney! Not only did they do most of the towing, they dug the Erie Canal, which made New York harbor the gateway to the west. In fact, it was because relatives here said “the Irish have most of the jobs in the ditch” that Thomas Moran, a 61-year-old unemployed stone mason from Kill Lara, County Westmeath, brought his family to America in 1850.

To say the Irish had a lot to do with making New York a great maritime port is no blarney! Not only did they do most of the towing, they dug the Erie Canal, which made New York harbor the gateway to the west. In fact, it was because relatives here said “the Irish have most of the jobs in the ditch” that Thomas Moran, a 61-year-old unemployed stone mason from Kill Lara, County Westmeath, brought his family to America in 1850.

It was Thomas’ second oldest son, blue-eyed, black-haired Michael, who had the vision and the big dreams while driving mules along the canal tow path.

Michael had arrived from Ireland, with his father, five brothers, and one sister (his mother died on the voyage over), and settled in Herkimer County in 1850. The boy was thirteen. He went to work driving the mules that walked alongside the Erie Canal pulling boats back and forth. It was, he felt, monotonous work for an adventurous spirit. Scenically, it had its limitations, and there was nobody to talk to, conversation with a mule being more or less one sided. He often reflected that although he was making some progress, he was making no more than the mules. After a few years of this, he decided, quite literally, that he was getting in a rut, so he bought a boat of his own. He first operated it on the canal, but he soon made occasional sorties down the Hudson, hauling mostly grain. By 1860 he had acquired several more boats and didn’t care if he never laid eyes on another mule. - From “The Elegant Tugboater” by Robert Lewis Taylor in the November 3, 1945 edition of The New Yorker Magazine.

By the time he was 22, he was operating his own towboat. Then, at 27, with his savings in his pocket, Michael said goodbye to his family and told his sweetheart he would be back to get her. He traveled down the Hudson on a grain barge with the dream of opening a towing brokerage office in a port teeming with shipping. For $10 a month, Michael rented a desk in a bar at 14 South Street and Moran Towing was born in New York harbor. Today it is the largest marine transportation company in the East and Gulf states.

The Commodore

Before Michael Moran brought order to the chaos of towing, many tugs would race to the mouth of the harbor for an approaching ship and wage a bidding war through megaphones. Sometimes it got physical, with tugboaters tossing shovels, frying pans, and anything else they could find to quiet their competitors. Michael decided tug-boaters might do better by banding together instead of battling on alone and soon he was handling towing for nearly 20 ship captains. He worked long hours and drove a hard bargain but gained a reputation for honesty. He soon bought two secondhand tugs of his own.

The tradition of Michael hovers over the company like a guardian angel. During his long tenancy he ran things with what is described in novels as an iron hand. He was bold but pious, and he tolerated no monkey business. He lived with his family in Red Hook, a region of Brooklyn whose forthright manners often caused him severe pain. - “The Elegant Tugboater,” Taylor

His years with the mules had given him a muscular outlook not always associated with piety. As his fleet of tugboats grew, he often found it necessary to use a fleshly approach in refining the general spirit. After years working with mules, Michael had developed a certain style of toughness to get through men’s stubborn habits. If he found his crew drunk and brawling, he would grab them and bang their heads together, while quoting scriptures and admonishing them. Michael was also impatient with profanity and ordered his crews to find substitutes for strong language. Experiments with “shucks” and “drat” didn’t last.

While Michael would brook no nonsense, he was described as gracious and compassionate. “No effort was ever spared to help anyone in need,” his grandson Edmond J. Moran said years later.

Business was good but Michael’s life was not yet complete, so in 1862 he went upstate and married Margaret Haggerty in St. Mary’s Church in Albany. He brought her back to an apartment in Red Hook, Brooklyn, near the Atlantic Docks where his tugs were kept. As his family expanded, Moran bought a house at 107 William Street (now Pioneer Street). Michael and Maggie had a daughter and five sons, each virtually weaned in the pilot house. Eugene, born in 1872, was the third child and would eventually run the family business. His brothers were Richard, William, Joseph, and Thomas, whose son Edmond would later succeed Eugene. Agnes married J. Frank Belford, who also worked in the company.

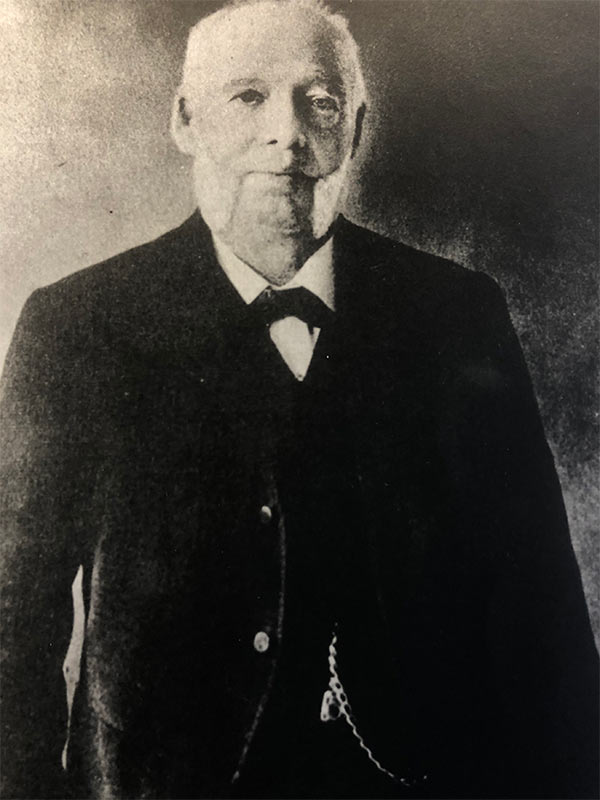

Michael was of medium height but his large frame made him appear bigger. He wore a black coat, kept open, and a heavy watch chain with a small compass bounced over his belly. “In his blue eyes a twinkle was usually lurking,” recalled his son Eugene. “He laughed a good deal.” His charm and savvy kept Michael on the good side of Tammany Hall at a time when New York was the largest Irish city in the world. He got the exclusive contract for moving the city’s garbage out to sea. A few years later, Moran tugs would tow away the excavated rock from the city’s first subway tunnels. At the 1889 centennial of the British evacuation of New York, Michael was designated the honorary commodore for tugs in a big marine parade. The title stuck, and fellow boatmen began calling him the “Commodore of the Irish Navy.”

Michael was good to his family and a question he proudly asked of the South Street cronies he brought home for dinner was: “How do you like my crew?” His first brand-new tug, the Maggie Moran, was named for his wife. “It was a great day for Father and Mother, as it was for us kids, when the tug was commissioned in 1881,” Eugene later wrote. “We climbed and poked over every nook of the vessel.” Sadly, Maggie Moran died two years later at age 42. Three of their sons would also precede Michael in death. Richard died of consumption at 26. Thomas died at 39 and William at 27.

A Reputation for Caution

From “The Elegant Tugboater” by Robert Lewis Taylor in the November 3, 1945 edition of The New Yorker Magazine:

The founder of the Moran company, despite his natural wish to make money as rapidly as possible, was a stickler for caution. He disliked taking chances with other people’s property; it offended his sense of thrift. Consequently, he expended an unusual amount of time drumming carefulness into his crews. On the surface, this extreme devotion to safety seemed gratuitous, but, as his successors agree, it has proved remunerative in the long run.

Rival tugboaters have occasionally called the Moran outfit sissified, but such trifles have caused no change in the company’s policy. In the early days of the business, some independently operated tugboats exhibited a festive, rakehell attitude toward their work. Abstractedly hooking on to a valuable cargo ship, they would swing gaily through the harbor, the whistle tied down, the captain drunk, and the crew playing seven-up in the galley. It was sometimes possible to trace their course by the deposits of paint left on the sides of such harbor furniture as buoys, docks, anchored ships, and other maritime objects. These boats, which have since disappeared from view – downward, for the most part – made both the elder Moran and his son Eugene shudder violently. Eugene Moran likes to point out that his company now has contracts with most of the steamship lines that operate the largest vessels. “It’s our reputation for taking pains,” he generally adds, looking vaguely like Michael.

The elder Moran (Michael) more or less retired in 1898, and in 1906 he died. Eugene became head of the company. For quite some time the new president’s technique, when faced with a decision was to say to himself, “How would Papa do it?,” and attempt to do likewise.

The Moran company has a safety record that tugboaters the world over admire. Moran (Eugene) likes to point out, with a laugh, that his safety record is no accident. It is rather, he feels, a heritage from his celebrated father, Michael Moran, who founded the company in 1860.